I was recently invited to give a lecture at the Fleming Museum at the University of Vermont as part of their special exhibition: Spirited Things – Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic. While I have given lots of presentations over the years, mostly on National Geographic ships, this was the most “academic” lecture I have given in many years.

At the request of some of the attendees I have posted the lecture below and tried to incorporate some of the audio-visual components as best I could in this context.

While I did present this lecture to the public, I definitely consider it a very rough draft. It is filled with flaws and errors both factual and stylistic, which I hope to correct someday. Until then, I hope this will be of interest.

+++++++

When the Spirit Moves Me: Music and Religion from Africa to the Americas

As is true for many people, my first exposure to the Afro-Cuban religion simplistically known as Santería came through music. When I was a student at Oberlin College in northern Ohio, I developed an interest in the music of Latin America (actually, my interest in the music of Latin America began with a girlfriend from Chile…but that’s a whole different story, and one my wife probably doesn’t want to hear repeated).

I heard that there was a significant Puerto Rican community in the nearby city of Lorain, a town whose social history was defined by the steel mill that attracted immigrants from all over the world. A friend gave me the name of a salsa band he’d heard of that played at local Puerto Rican community events.

They were called Orquesta Tuyeré. After a little sleuthing, I managed to get the name and phone number of the bandleader, a steelworker and union leader named Dominic Cataldo…Like me, Dominic wasn’t of Puerto Rican heritage, but he had fallen in love with the music and then with the culture and then with a Puerto Rican woman whom he married. I learned later that Tuyeré is not a Spanish word, Dominic decided to name the band after a specific pipe in the steel mill that was particularly challenging to fix…a reflection of his struggles to master the complexities of Puerto Rican and Cuban music. It turned out, and this seems to be common for salsa bands all over the world, while drummers are a dime a dozen, horn players, a necessity in any good salsa band, are in high demand. Even though I was a pretty mediocre trumpet player, I soon found myself playing in his band and eventually other local Latin dance bands in the Cleveland metro area.

Margie & La Nueva Banda, one of the groups I played with in Lorain. I’m in the center back holding the trumpet, younger (and thinner) then I am today.

Margie & La Nueva Banda, one of the groups I played with in Lorain. I’m in the center back holding the trumpet, younger (and thinner) then I am today.

So there I was, a white, Jewish guy from Vermont, dancing (poorly) and playing (only slightly less poorly) at the Puerto Rican social club of Lorain, Ohio, a run down and nondescript brick building in the shadows of the steel mill.

El Hogar Puertorriqueño – The Puerto Rican Social Club in Lorain, Ohio (Source: Google Street View)

El Hogar Puertorriqueño – The Puerto Rican Social Club in Lorain, Ohio (Source: Google Street View)

Even though the mill, like so many American steel mills, no longer employed many people, flames still shot up from the blast furnace chimneys, even at night, serving as a fiery backdrop to the Puerto Rican dance parties. This was a decidedly secular setting…the men wore fancy polyester shirts with flowery designs and the ladies squeezed themselves into tight, sequined dresses and high heels. People drowned their daily troubles in drink and dancing.

This was the time, the eighties, when salsa erotica was all the rage. Songs with titles like “Ven, Devorame Otra Vez” (Come, Devour me again) and “Quiero llenarte toda” (I want to fill you all the way) were pretty clear in their intentions and where the night would hopefully lead.

Yet peppered amidst the romantic salsa tunes and upbeat merengues, I heard references to more profound subjects. There were often lyrics that clearly weren’t Spanish…they sounded African, but when I asked what they meant even the singers couldn’t really translate them. Names like “Chango”, “Babalu Aye”, “Yemaya” appeared regularly, often shouted out for emphasis. And every once in a while, there would be a rhythmic breakdown, a point at which the song would shift into a more complex 6/8 rhythm and everything seemed to get much more intense and powerful. The percussionists stopped looking bored and got into a groove, showing off their rhythmic firepower. Even the dancing seemed to get more serious…this was when fluffy stuff was put aside and the serious, hardcore dancing began. Dancers bent their knees, crouching down a little closer to the floor, and focusing less on fancy footwork and more on showing some soul. Eventually, we all shifted back to the schmaltzy lyrics and cheesy melodies. But during those intense musical moments, I knew something different was happening, something deeper and more heartfelt. I just didn’t know yet what it was or where it came from.

After a while, when the other members of the band felt closer to the stranger in their midst, I started to hear talk from the drummers about toques. As it turned out, besides playing in salsa bands, some of the more accomplished drummers were hired to play at ceremonies for a religion called Santeria…the worship of the saints. What these ceremonies where, and where and when they took place was kept very private. I could tell, this was secretive stuff and intended only for people who were authentically involved with the religion. In fact, the secretive part seemed to be part of the appeal, it was like a private club and in order to be allowed in you had to prove your sincerity and earn your dues.

These toques were also only for very serious musicians. Santeria drumming was far more complicated then salsa and merengue. It required years of training on the batá, hourglass shaped drums that allowed for intricate rhythms designed specifically to communicate with particular orishas, or saints.

A set of batá drums

A set of batá drums

Batá drumming is an essential element of Santería ceremonies, it is through the drums that the spirits are called, specific patterns for individual saints, encouraging them to possess one of the believers and make their presence felt. Given its specialized training and complexities, a skilled drummer can make decent money being hired to play at these events.

As I learned more about Santería, the more I started to notice other references to it. In addition to constant mentions in songs, I noticed a number of botánicas in Lorain and Cleveland.

A botánica in Lorain, Ohio (Source: Google Street View)

A botánica in Lorain, Ohio (Source: Google Street View)

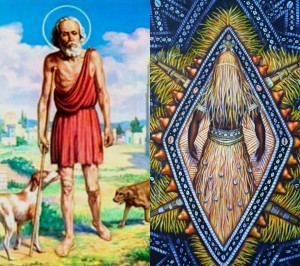

These are shops that sell candles, statues, medicinal herbs and religious items. Most of the iconography in these botánicas was Catholic…statues of St. Lazarus as a poor beggar, his wounds being licked by dogs. A beatific Mary, dressed in blue. The candles often had specific conditions written on them, the idea being that burning them would help attract a lover, fix a heart condition, win a court case, earn some money.

Botanicas also sold music, at that time on cassette, mostly of religious music, and it was at a botanica in Cleveland that I bought my first Celina & Reutilio album.

I’m not sure what I expected, but it wasn’t African drumming and it wasn’t spiritual chants, that’s for sure. This was party music for the saints…music to get your feet moving and fill your spirit with joy. Yet the lyrics were a mix of Spanish and Yoruba languages, with passionate references to the orishas. “Long live, Changó”, Celina would sing, blending the rootsy sound of Cuban guajira music of the countryside with Santeria chants. Suddenly, Santeria didn’t seem so secretive anymore…the music opened the door and welcomed me in. I may not have been a believer, but the music still moved me.

Eventually, my folklore professor at Oberlin received a grant to study Afro-Cuban religious expressions in northern Ohio. She brought me on as a research assistant (mostly, I think, because of the personal connections I had cultivated through the music scene) and we spent one summer interviewing musicians, worshipers and even non-believers in the community for their take on the practice. Some people saw it as superstition; hocus pocus; a cult that had no real power. Others believed it connected them to their African roots, Santeria was a way to reclaim and celebrate their identity. Others didn’t want to talk about it, for fear of making someone upset or revealing too much. But even with people who dismissed it, there was respect and an attitude that even if Santeria was just superstition, it was better to be safe then sorry.

The first time I truly appreciated the power of Santeria and the impact it had on people was when we visited the home of a Cuban worshipper in Cleveland that many of my friends pointed to as “the real deal”. He was a ‘marielito”, part of the 1980 Mariel boat lift that had brought thousands of Castro’s castoffs to the states. He spoke very little English and he lived in a rough part of town. We climbed the rickety old stairs entered his apartment: it was like entering another world. Each room was filled with altars, religious objects, statues, candles, bottles of rum, sculptures.

It was an explosion of color and texture…even the kitchen counters were covered….with Barbie dolls, matchbox cars, stuffed animals and other everyday items that had been repurposed as orishas or symbols. There appeared to be no room for him to sleep or eat, although he must have found a way. Imagine entering the apartment of a hoarder, but in this case, every item had symbolic significance…and power.

In the middle of one room was a large cauldron with swords and other metal objects sticking out of it.

He lifted the lid, and cockroaches scurried out. I’ll be honest, a chill went down my spine. I knew this was something meaningful, something that embodied a deep spiritual energy. I learned later that in Afr0-Cuban religion, the cauldron is the symbol of the orisha Ogún.

The lord of metals, Ogun is known for his brusque personality, but he tempers it with a more peaceful side. He is a good farmer, animal breeder and hunter, and he knows the secrets of the natural world. He’s also known as the champion of the working man. Every practitioner of Santeria identifies with a particular spirit, and in the case of our host, his spirit was Ogún. I had the feeling that we were the first outsiders he had invited into his home, and the first to show us his most sacred altar.

From that day on, while I remain an unabashed atheist, I have felt a tremendous amount of respect for Santería, Vodun, Candomblé and other African religious expressions in the Americas. And over the next 30 or so years, as I have spent time working with musicians from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil, Trinidad, Belize, and, various West African countries, the impact of these beliefs, their complexities and the important role they play in maintaining cultural heritage and tying communities together has become ever more apparent.

I’d like to remind you all that this story I just told took place in northern Ohio, not some remote Caribbean village. For this Cuban guy who had been relocated to a cold city far from his beloved island home, his religion kept him connected to his roots, his ancestors and his culture.

I have since come across Santeria communities in many other places I have visited in the US, not to mention across Latin America and the Caribbean. These and other African religions have far more followers than most Americans realize, and there has long been a great amount of fear, misunderstanding and over-simplification of these beliefs. As time goes on, these religions continue to emerge from the shadows and earn respect and appreciation. And as I will discuss, music has played an essential role in the practice, maintenance and promotion of traditional African religious beliefs in the Americas. The influence of these ancient spiritual practices can be felt today in the popular music and mainstream culture of any country with an African population.

A Mongolian shaman using a frame drum (Photo by Alexander Nikolsky)

A Mongolian shaman using a frame drum (Photo by Alexander Nikolsky)

There has been an intimate connection between religion and music that almost certainly dates back to the dawn of humanity. Ancient cultures used music to communicate with the gods, and among a shaman or medicine man’s most powerful tools where the drums, rattles and whistles that facilitated this conversation.

For many religions, entering into a trance is the precursor to a state of higher consciousness that allows for a deeper connection to the astral plane, to altered states where higher powers reside. It could be the steady beat of a drum around a campfire, a Buddhist chant or a heavenly choir in a European cathedral…all are examples of music that help us enter a more open mental state for religious communion.

Music is also an important tool for passing on religious doctrine. Songs help people remember complex lines of text, or precise incantations, and music has long played a role in facilitating oral tradition.

A singer at a church in Corsica (Photo by Jacob Edgar)

A singer at a church in Corsica (Photo by Jacob Edgar)

While religion is personal, it is also communal, and there is no better tool for fostering this sense of community than music. When people sing together in one voice, it binds them like nothing else can.

Musicians and dancers in Lobito, Angola (Photo by Jacob Edgar)

Musicians and dancers in Lobito, Angola (Photo by Jacob Edgar)

Religion is also an outlet for deep human emotion…and music is one of the best ways of expressing that emotion. Music exists beyond words, it is an art form that reaches deeply into our soul…who among us has not shed a tear at some point when hearing a song that moved us, or been lifted to our feet to dance in joy when an irresistible beat beckoned us?

In the African religions of the Americas, music has played all of these roles and more. Indeed, without music to sustain them, it’s possible that these religious expressions would have died out completely among the descendants of Africa in the New World.

The transatlantic slave trade lasted over two hundred years, starting in the late 1600s and ending in the second half of the 1800s, depending on the country. During that time 10 to 15 million Africans were brought in chains and with no possessions to a strange and oppressive world.

Separated from their communities, families and way of life, all they carried were intangible cultural expressions such as language, tradition, spiritual beliefs, dance and music. In most cases, they were forbidden from overtly cultural demonstrations, so they came up with creative ways to maintain these traditions and beliefs in ways that would be accepted by their overlords.

Africa is not a monoculture. Indeed, it is one of most culturally diverse regions on the planet, with hundreds of languages and a wide variety of social and political structures. This diversity extends to spiritual beliefs as well as, of course, to music.

So the Africans who were brought to the Americas represented a range of religious traditions, each with their own unique deities, rituals and core beliefs. There are, however, some common elements, which have also been passed down to the surviving expressions in the New World.

While many traditional West African religions do subscribe to a belief in a single supreme creator, they also revere a number of spirits or saints, each with their own personalities and identifying characteristics. Religious ceremonies almost always involved dance and drumming that would lead to trance states with the goal of encouraging one of the spirits to possess the practitioner and thus reveal him or herself to our world. Reverence for ancestors played a central role and in many cases ancestral spirits continued to impact the contemporary world.

Traditional West African religions usually feature healers or shamans that use their knowledge for medicinal purposes, to divine the future or to impact real-world events. West African beliefs were oral traditions, meaning they were passed on through demonstration rather then through written scriptures, testaments or doctrines.

As such, I should point out that makes it much more difficult to determine how old these traditions are, and how much they have changed or not over time. And because they were so poorly documented or understood by outsiders, not to mention the impact of Christianity, Islam and even Judaism on the African continent today, its also hard to say how closely modern expressions of African religions in the Americas reflect authentic African traditions and how much they have been adapted to their new circumstances, romanticized or been subject to other outside forces.

Once Africans arrived in the New World, their traditional religious practices were forbidden, seen as backward superstition by the colonial rulers. These attitudes continue to this day, as voodoo dolls, ritual sacrifice and witch doctors remain popular stereotypes, Halloween tropes and horror movie scare tactics.

Most of Latin America was Catholic, which in a strange twist of historical fate, turned out to be a surprisingly flexible religion. African slaves soon figured out that there were some common elements between Catholicism and traditional African religions that allowed for some subterfuge.

African spirits could be paired up with Catholic saints. In Cuba, for example, Chango, the orisha of thunder, fire and virility, took on Saint Barbara as an alter ego.

Babalu Aye, Orisha of healing, became St. Lazarus whose wounds were healed by divine intervention. The list goes on.

Traditional African religions give great resonance to physical objects as manifestations of spiritual energy. These could be hidden as Catholic religious icons and symbols, thus allowing for altars that incorporated a fascinating blend of Catholic and West African iconography.

The Catholic festival of Carnevale, which originated as a last hurrah of indulgence before the 40 day period of fasting and abstinence of Lent, became the one time of the year when Africans were allowed to express themselves.

They took this small opening and turned it into the colorful bacchanal of Carnival, aka Mardi Gras that explodes across Latin America and the Caribbean every February or March. I don’t need to mention how important music is to this religious festival, indeed African music and spirituality have hijacked these events transforming these Catholic holidays into powerful celebrations of African culture in the Americas.

The blending of Catholic and West African beliefs is an example of what’s called syncretism. The best-known syncretic religions of the Americas include Cuban Santeria, Haitian Vodun and Brazilian Candomble, but there are many lesser-known types, including Jamaican Kuminá, Winti in Suriname and Dugu among the Garifuna community of Central America. Each of these religions have their own musical styles and practices, but they are united by common African features such as the central role of the drum and percussion, call and response singing, communal dancing, repetitive and cyclical song cycles that encourage improvisation and personal expression over rigid structure.

This concept of syncretism, or mixture, is reflected in the music of the Americas as well. African rhythms, instruments and styles have been blended over the centuries with European ballroom dances, military brass bands and folk music. These cultural blends have led to most of the popular music we listen to today, from the blues and rock and roll, to jazz, hip-hop, salsa, samba, tango, funk and so much more.

British colonies, such as America, largely followed Protestantism, which turned out to be much less flexible then Catholicism in terms of allowing for unique African expressions. This is one reason we see fewer overt examples of syncretism in the United States today, except in traditionally Catholic areas such as Louisiana.

Even so, evidence of African religious traditions can still be felt in African-American churches. While Protestantism did not leave room for African deities and icons, it could not hold back the physical communal expression and trancelike states induced by gospel music.

Another reason we see less overt syncretism in the United States is purely demographic. A lot of Americans don’t realize this, but slavery was actually much less prevalent in the US then in other parts of the Americas. In countries such as Cuba, Brazil, Haiti and others, a much larger overall portion of the population consisted of Africans and their descendants. In America, we have come to recognize the central role African-Americans have played in forming our nation’s identity. Imagine how much greater that contribution is in countries such as Brazil, Cuba or Haiti, where African culture is not a minority…its part of the family tree of most citizens.

Music helped with this syncretism, providing the camouflage that kept African religious beliefs hidden under an acceptable veil. While drumming and dancing were discouraged, they were often allowed in order to placate restless slaves, or overlooked when heads where turned. While initially, Europeans reacted with horror at the physicality of African music and dance, they soon became intrigued by it, and African music was quickly impacting popular music across the Americas and even back in Europe. Because of the secular and spiritual duality of drumming, and the lack of understanding by the rulers, performers where able to incorporate religious rhythms overtly into their daily musical practice.

As in Africa, music played an essential role in the passing on of oral tradition, allowing the descendants of African slaves to retain aspects of their language, traditions and identity much longer then they might have been able to otherwise. The music of Santeria and other syncretic religions kept West African languages alive in the minds of the population. Even if people couldn’t communicate through speaking, they could retain elements of their native languages through their use in music. Origin myths, cultural histories and folktales are passed on through music. Music also continued to play an essential role in the ritual context of African religions. As was the case with the toques in Cleveland, a traditional African religious ceremony without music is completely unheard of…Indeed, without music to attract the deities, they would likely have never appeared.

Conversely, African religious expression has turned up regularly in secular popular culture. While ceremonies were restricted to the private realm, references to African religious beliefs and deities have been appearing regularly in commercial recorded music since the 1920s, if not earlier.

In Cuba in the 1920s, for example, musical ensembles known as sextetos or sextets began to form, performing mostly a style of dance music called “son” which has since gone on to serve as the foundation for contemporary salsa music. Included among the sextet’s instrumentation was a double headed drum called the bongó. While not used in Santeria ceremonies, the sound of the bongo allowed drummers to emulate some of the sounds and rhythms of the batá drums.

In 1927, Ignacio Piñeiro added a trumpet to his lineup, forming the first septet and marking the beginning of the key relationship between brass instruments and Latin popular music. Septeto Nacional‘s 1928 song “Mayeya, No Jueges Con Los Santos” (Mayeya, don’t toy with the spirits) directly referenced Santeria and was a popular and enduring hit for the band. “Mayeya,” he sings, “don’t deceive me. Respect the necklaces, do not toy with the spirits.” He goes on “He who does not wear yellow covers himself in blue,” referencing to the yellow of the orisha Changó and blue for the orisha Yemayá.

As writer Ned Sublette points out in his book Cuba and its Music, “It may be difficult to appreciate, nearly a century later, how unsettling and even threatening it was for the refined classes of Havana to hear the sounds of brujeria (witchcraft) in popular music; think of how gangsta rap sounded to polite American society seventy years later.”

Because of its religious connotations and the fact that it was played with hands and not sticks (European drums were allowed as they were played with sticks), there was even a law passed at one point requiring the use of sticks when playing the bongó. Eventually, “bongos” became accepted…to the point where thirty years later it was part of the image of the Lower East side beatnik, reading poetry in a beret accompanied by bad bongo playing.

And overt references to Afro-Cuban religions not only became more visible, they became exoticized by artists in the 1950s. Here’s Cuban-American TV star Desi Arnaz, aka Ricky Ricardo from I Love Lucy, performing one of his signature songs. He calls out, “Babalu”, a reference to the orisha Babalu Aye.

By the 1950s, African religions in the Americas had moved from the shadows into a place of parody and stereotypes.

Haitian Vodun, aka voodoo, especially its notion of zombies, or the dead who have been reanimated through magic, became a staple of horror movies. The voodoo doll was out of the bag, so to speak.

Even when respectful and accurate attempts were made to portray African religious ceremonies, they still were used to spook viewers. This Brazilian Macumba scene from the 1959 Academy Award-winning film Black Orpheus actually does a good job of portraying the authentic power and beauty of Afro-Brazilian possession ceremonies, but when seen by a foreign viewer with no context or explanation, it is ripe for misunderstanding and misinterpretation.

Compare that representation to this one from the 1973 James Bond film, Live and Let Die. Set in the fictional Caribbean island of San Monique.

Music played a role in this misrepresentation of African religions. The popularity of Caribbean music sparked by singers such as Harry Belafonte in the 1950s, led to a wave of imitators, many of whom used sensationalism and parody in an effort to reach mainstream audiences.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3867948-1347467125-1189.jpeg.jpg)

While Belafonte generally approached Caribbean folklore with respect and reverence, even he took part in some pretty goofy representations of the zombie myth and African culture.

By the 1960s, however, identity movements across the Americas sparked a reexamination of African heritage. African-Americans began to express pride in their African roots, and music was one of the tools they used to express that pride.

The 1960s and 70s salsa scene, whose epicenter was among the Puerto Rican community of New York, approached Afro-Cuban religions with more respect.

They incorporated imagery on their album covers that reflected that pride, and rather then catering to the simplistic stereotypes of audiences outside of their communities, they began to use Afro-Cuban religious terminology and rhythms in a studied way.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7257032-1441337747-1086.jpeg.jpg)

Meanwhile, back in Cuba, Santeria, which was initially frowned upon by the Castro revolutionaries, became reclaimed as a symbol of identity. In a country where religion was viewed by Marxist revolutionaries as “the opiate of the masses”, Santeria developed into an authentic expression of Cuba’s working class cultural roots…it was the voice of the people, not the oppressors.

This sparked a boom of Afro-Cuban influence in local music. The Cuban supergroup Irakere, became one of the first to use the batá drums in a secular musical setting, inspiring a wave of international interest in the style:

By the 1980s, the complex rhythms of Afro-Cuban religions had permeated and diversified Cuban popular music. Here’s NG La Banda, one of Cuba’s pioneering timba bands, reinterpreting “Que Viva Chango” the song I loved so much from Celina y Reutilio. They give it a sophisticated, virtuosic arrangement that brings Santeria sentiments into a modern context:

The same thing was happening across Latin America. In Brazil in the 1970s and 80s, samba singer Clara Nunes, a devotee of the Umbanda religion, brought Afro-Brazilian culture to the mainstream, becoming the first Brazilian artist to sell over 100,000 copies of a record. She was a devoted student, traveling often to Africa for research, and she helped popularize the notion that in Brazil, everyone had African roots no matter the shade of their skin.

On her song “Tribute to the Orixas”, Nunes calls to the African deities, singing “Brought by slave ships, From the African soil to the Brazilian fields. The black slaves, between groans of pain and tears. They brought in their suffering hearts, what is today so venerated in Brazil, the rituals of Umbanda and Candomble.” Then she pays tribute to the orixas, calling them out by name and character. It’s a powerful message: direct, to the point, yet beautifully poetic.

By the 1990s, this reevaluation of African heritage led to the formation of afoxés, or blocos afros in Salvador, Brazil’s most African city and a world musical hotspot. Some researchers have referred to afoxé as Candomblé with the religion taken out of it.

During carnival in Salvador, Candomblé rhythms and songs are performed by ensembles of hundreds of people, parading down the streets in costumes derived from traditional Afro-Brazilian ceremonies and imagery. This is the bloco afro called Ile Aiye, which was formed specifically to celebrate African culture in Brazil:

The power of hundreds of people drumming together sent a powerful message of community and heritage. Not to mention rhythmic virtuosity, a hand me down from African music. This is a clip featuring the afoxé band Timbalada, it was filmed for the Imax film Pulse: A Stomp Odyssey:

A more commercial style of carnival music developed that came to be known as axé, a Yoruba word meaning “soul, light, spirit or good vibrations”. Axé is also used in Candomblé to describe spiritual power bestowed by the orixas. The music is called axé not so much for its specific musical elements, but because of its direct connection to African spirituality and identity.

Even axe’s most popular light-skinned artists such as Ivete Sangalo and Daniela Mercury celebrate the African roots of their music…its what gives it cred.

Today in Brazil, African culture and religion is celebrated by people of all shades and backgrounds, thanks in large part to its exposure through popular music.

Haiti offers a unique perspective, as it was the only country in the Americas where a slave uprising led to the defeat of colonial powers and full independence in 1804. There are plenty of Haitians today who attribute their victory over the French to the powers bestowed upon them by the African Vodoun deities.

Because of their early independence, Haiti is home to some of the strongest African cultural retentions in the Americas, and even though most people consider themselves Roman Catholic, they are also firm believers in Vodoun. Vodoun imagery is everywhere in Haiti, and that is reflected in its popular music, especially in the last 30 years or so as Haitians have sought to celebrate their African cultural roots.

Musical groups such as Bouken Ginen, Boukman Experyans and RAM have incorporated Vodoun ceremonial instrumentation, wardrobe, references and iconography into their sound. This musical movement is known as “racine” or roots, for obvious reasons.

I’ve personally had the pleasure of working with one of the hot new bands in the Haitian music scene, Lakou Mizik.

Lakou Mizik performs hours long concerts that blend the soulful spirit of a church revival, the social engagement of a political rally and the trance-inducing intoxication of a vodou ritual. The band Lakou Mizik considers it a mission to bring Haitian traditions to wider audiences and to keep it vibrant and alive among young people.

One of the band’s core members, Sanba Zao is a legend of the racine (roots) music movement in Haiti and a vodoun acolyte. He is a master drummer with an encyclopedic knowledge of traditional songs and rhythms; Zao’s deep knowledge of traditions immediately gave youthful rebirth to old songs that had long been relegated to the archives.

In Haitian Kreyol the word lakou carries multiple meanings. It can mean the backyard, a gathering place where people come to sing and dance, to debate or share a meal. It also means “home” or “where you are from,” which in Haiti is a place filled by the ancestral spirits of all others that were born there. Each branch of the Vodoun religion has its own holy place, called a lakou, where practitioners may come together in the shade of a sacred Mapou tree.

Last year, as part of their effort to bring Afro-Haitian traditions to a young audience, Lakou Mizik teamed up with the Haitian electronic music DJ Michael Brun to collaborate on the carnival song “Gaya”. While intended for mass audiences, the song craft fully blends old and new, making a connection between Haiti’s deep African roots and new technology. It’s title means “Healing” in Haiti’s Kreyol, and the lyrics tell the story of a unified people full of pride and positivity.

I have also had the good fortune to work with musicians from the unique Afro-Amerindian Garifuna culture of Central America, specifically the Caribbean coast of Belize, Honduras and Guatemala. The descendants of African captives who were shipwrecked in the Caribbean in 1635 and intermarried with local Arawak and Carib Indian populations, the Garifuna have a distinct language and culture as well as unique religious practices and enchanting music.

Garifuna styles, such as the Latin-influenced paranda, the sacred dügü, punta and gunjei rhythms, have been reimagined by contemporary Garifuna musicians such as the late Andy Palacio, leading to a revival of tradition in the Garifuna community.

When Andy passed away unexpectedly in 2008, he was honored with a traditional Garifuna “NineNight” ceremony, in which family and friends say farewell to the spirit (Ahari) of the deceased. The wake lasts for nine days of singing, drumming and dancing. It is only after that ceremony that the trip to the other world begins.

I could speak for hours on Andy and the Garifuna, but unfortunately that will have to be the subject of a future presentation.

Today, African religions in the Americas have come out of the closet. For centuries they have been scorned, misunderstood, and marginalized. In response, they developed a culture of secrecy and mystery, which, while adding to misconceptions, helped retain some of the power they had lost when they became the religions of a subjugated community.

Music has played a core role in the practice and ideology of these religions, not to mention being an essential factor in their preservation and survival over the centuries. Now that these religions are no longer conducted in secrecy, will they lose some of their power? What role can music play going forward in keeping these religions alive and meaningful into the future?

Of course, there remains a great deal of animosity towards African religion and culture across the Americas. As I was preparing for this lecture, for example, I came across a number of internet sites claiming that the song and music video for the big summer hit “Despacito” contains subliminal Satanic messages because of its use of lyrical and visual references to Santeria in the song and music video. Pretty silly, but a sign of how far African religions in the Americas still have to go to be understood and appreciated.

The sacred Mapou tree of the Haitian lakou provides an apt symbol for the African religions of the Americas. These are belief systems whose roots stretch deep into the past, across the ocean to the continent where these belief systems were born. They are supported by a solid trunk of community, faith and tradition. And their branches spread far and wide, connecting an African diaspora from Brazil to Belize, Cuba to…Cleveland.

This tree has survived oppression, war, brutality, neglect, discrimination, modernization, globalization, and disasters both natural and manmade. It seems likely to survive far into the future. And at the base of this tree, there has always been and will continue to be a drum beating, calling out to the spirits and beckoning them to join us in our world, to share their stories, wisdom, strength and inspiration for generations to come.